When Piaget bought Heuer

What an unlikely corporate transaction in the early 80s tells us about the quartz crisis – and how it shaped modern watchmaking.

I am on a plane somewhere over the Atlantic.

I’m watching The Living Daylights, a James Bond movie released in 1987. A comfort blanket of a film for me.

About an hour in, I almost jump out of my seat.

Because there on the wrist of General Leonid Pushkin, a key Bond adversary in the movie, is a Heuer Airline 24 H GMT (ref. 895.313) being used to secretly summon a bodyguard.

Timothy Dalton wearing a Heuer 1000 “Night Diver” (ref. 980.031) in Living Daylights is established lore.

But what I hadn’t clocked on previous viewings was that a number of the other actors in this movie also sport Heuer – and that this oddball Airline plays a starring role.

The Airline 24 H GMT is impossible to miss. Its bracelet features city names printed on the links like they’re passport stamps.

It launched during a period of Heuer’s history that rarely gets discussed: when the Piaget group acquired Heuer, owned it for a few years, then sold it to Techniques d’ Avant Garde (TAG).

Piaget’s brief acquisition and rapid divestment of Heuer is a convoluted tale of corporate shenanigans. But it’s also the story of how the quartz crisis shaped the modern world of watchmaking as we know it today.

What’s more is that Piaget didn’t even really want to buy Heuer; they were after something else: the world’s thinnest mechanical movement, made by an obscure manufacturer caught up in the deal.

And that pursuit ended with them accidentally overseeing the design of that most iconic of TAG Heuer watches, the Formula 1.

Heuer hurting

In the late 70s and early 80s, Heuer was in trouble.

The arrival of inexpensive quartz watches, the appreciation of the Swiss franc against the dollar, manufacturing mishaps and more conspired to put the company in real financial peril.

We know this because Jack Heuer tells us so in his excellent autobiography, The Times of my Life.

It’s packed full of interesting stories but the section detailing the end of the Heuer family’s ownership of the company is possibly the most fascinating – if not a little sad.

In it Jack points the finger at Valentin Piaget as the shadowy puppet master behind the takeover of Heuer in 1982 that pushed him out.

“Looking back, one of the very few things I have never forgiven is the fact that Valentin Piaget, who was pulling the strings behind the scenes throughout this takeover poker, had neither the courage nor the decency to approach me before, during or after the meeting to exchange a few words – the minimum courtesy one would have expected from a fellow entrepreneur.”

What Jack’s autobiography doesn’t really explain is why Piaget wanted Heuer at all. It looks like a total mismatch, which is why this story is so good.

Why did Piaget buy Heuer?

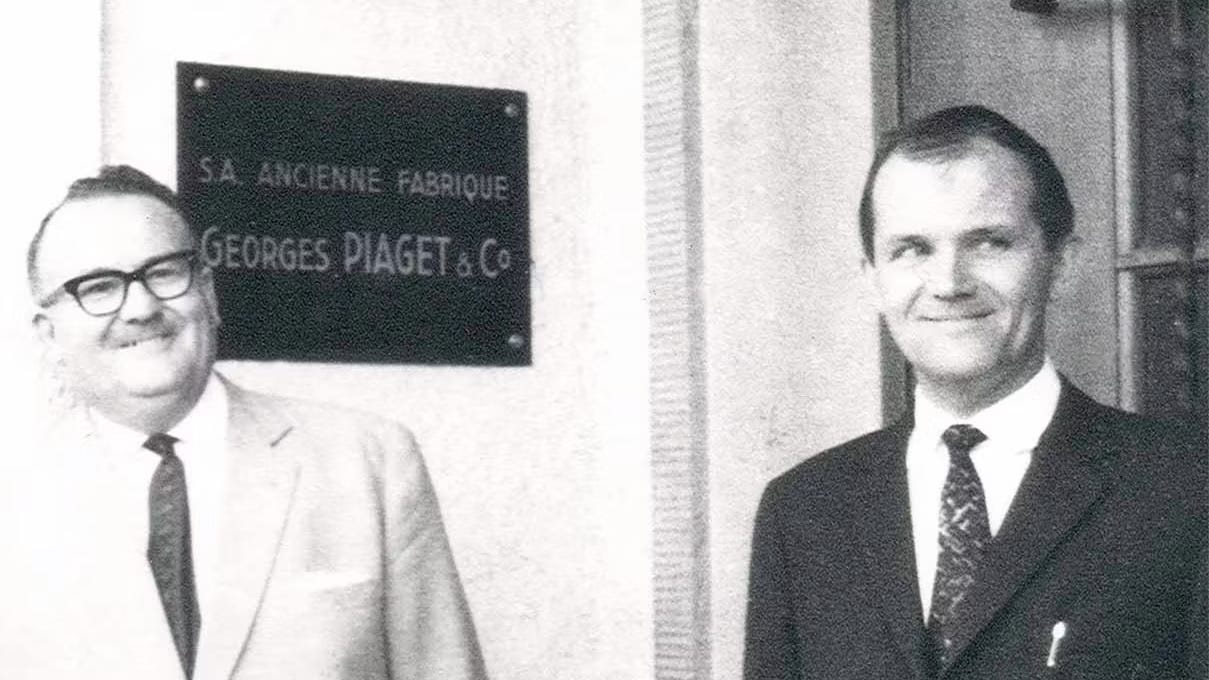

Valentin Piaget passed away at the age of 95 in 2017. He was the grandson of founder Georges-Edouard Piaget.

In 1945, Valentin and his brother Gerald took over running the family business. Gerald became CEO; Valentin focused on product.

He oversaw the development of the ultra-thin calibres 9P (hand-wound) and 12P (automatic) in 1957 and 1960 respectively.

His focus on the ultra-thin not only came to define Piaget’s watchmaking – it also provides the breadcrumbs as to why product-guy Valentin, rather than CEO Gerald, was behind the acquisition of Heuer for the family business.

You see I don’t believe Piaget was that interested in Heuer – it was storied movement-maker Lemania that really wanted Heuer. And the Piaget group just happened to have a controlling stake in Lemania at the time the deal went down.

So to understand why Piaget “bought” Heuer you need to first understand why Piaget might have invested in Lemania.

Lemania logic

Lemania is a manufacturer with a fascinating history.

It’s one of the most important mechanical chronograph makers ever. And in the early 80s, that was an endangered business thanks to quartz.

Chronographs weren’t merely fancy complications at the time; they were precision timing instruments.

So when a technology came along that offered more precision – at a cheaper price – mechanical chronograph-making probably didn’t feel like the best trade to be in.

In the early 80s, Société Suisse pour l’Industrie Horlogére (SSIH) decided to divest of Lemania – a company that had been part of its group (alongside Omega and Tissot) since the 1930s. At one point it seemed like the manufacturer might close entirely.

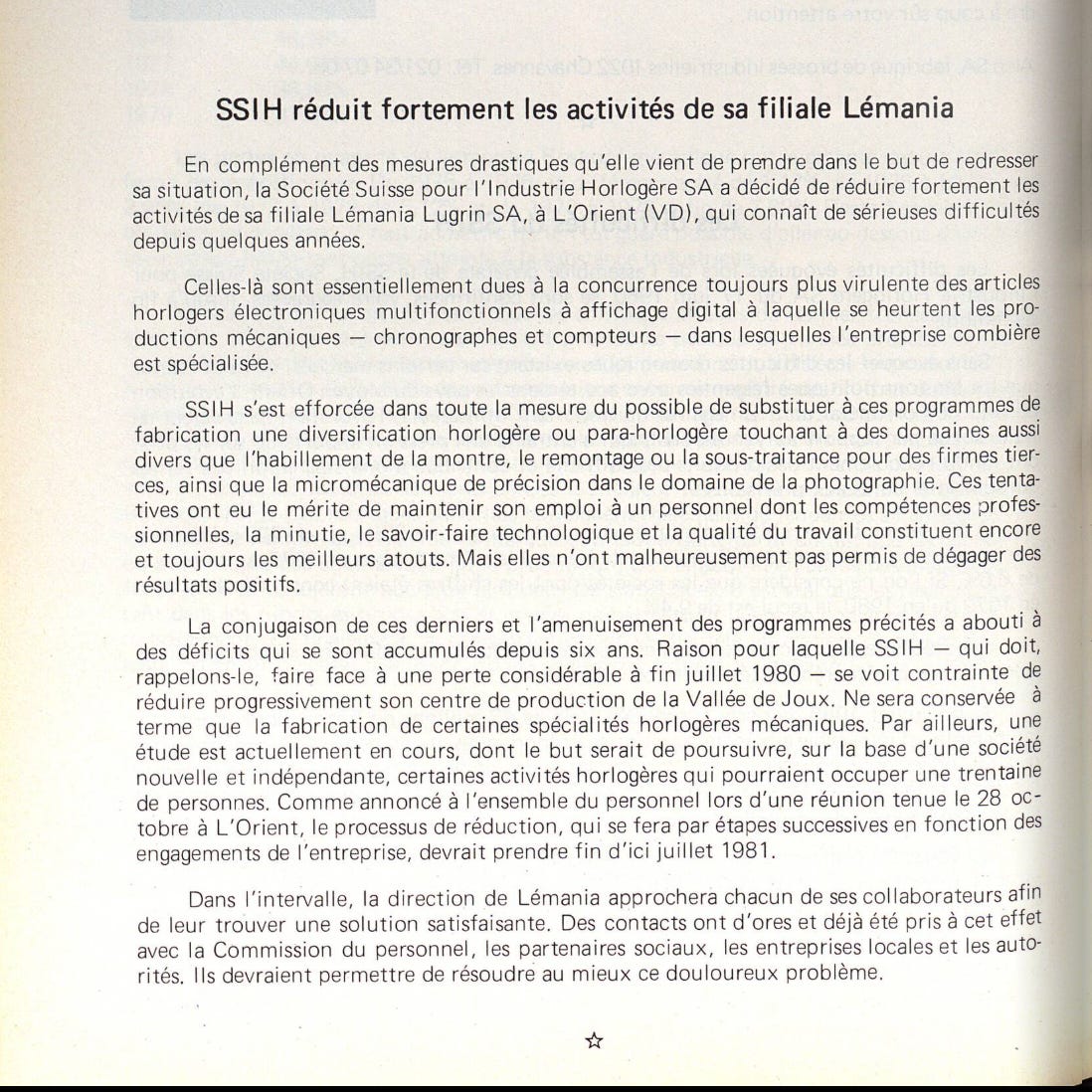

“SSIH drastically reduces the activities of its subsidiary Lémania

In addition to the drastic measures it has just taken in order to restore its financial situation, the Société Suisse pour l’Industrie Horlogère SA (SSIH) has decided to sharply reduce the activities of its subsidiary Lémania Lugrin SA, in L’Orient (VD), which has been facing serious difficulties for several years.

These difficulties are essentially due to the increasingly fierce competition from multifunction electronic watch products with digital displays, against which mechanical productions – chronographs and counters – in which the company is nevertheless specialized, have been struggling.

SSIH has made every possible effort to replace these manufacturing programs with diversification in watchmaking or related fields, touching on areas as varied as watch casing, movement assembly, or subcontracting for third-party firms, as well as precision micromechanics in the field of photography. These attempts had the merit of maintaining employment for a workforce whose professional skills, precision, technological know-how, and quality of work remain among its greatest strengths. Unfortunately, however, they did not make it possible to generate positive results.

The combination of these factors and the reduction of the aforementioned programs has led to deficits that have accumulated over the past six years. For this reason, SSIH – which, it should be recalled, had to face a considerable loss at the end of July 1980 – is now forced to progressively reduce its production center in the Vallée de Joux. In the long term, only the manufacture of certain mechanical watchmaking specialties will be retained. Moreover, a study is currently underway with the aim of continuing, on the basis of a new and independent company, certain watchmaking activities that could employ around thirty people. As announced to all staff during a meeting held on October 28 in L’Orient, the reduction process, which will take place in successive stages depending on the company’s commitments, should be completed by July 1981.”

In the meantime, Lémania’s management will approach each of its employees in order to find a satisfactory solution for them. Contacts have already been made for this purpose with the staff commission, social partners, local companies, and the authorities. These steps should make it possible to resolve this painful problem as effectively as possible.”

In 1981 SSIH sold Lemania to its own management team, keeping the company alive and installing Claude Burkhalter as Managing Director. The management buyout is well-documented.

What’s less clearly documented is Piaget’s backing of the buyout.

But in Jack Heuer’s account of the extraordinary meeting of shareholders in June 1982 where he was ousted, he shares an article from Neue Zürcher Zeitung, a Swiss German-language daily newspaper, which offers some insight as to how the Piaget group was operating at the time.

“When questions were raised at the press briefing after the general meeting about performance data and details about the owners, members of the top management were extremely tight-lipped.

However, there are clear grounds to believe that the funds which within the past year were invested in the purchase and restructuring of Lemania and now in the recapitalisation of [Heuer] have come from Piaget, the world-famous company known for its luxury and jewellery watches.

The interests of the Piaget Group are not confined to the joint-stock company Ancienne Fabrique Georges Piaget & Cie. in La-Côte-aux-Fées in the Canton of Neuchâtel, which declares a share capital of only CHF 128,000 but which last year paid tax on a profit of CHF 6.8 million (previous year: CHF 5.4 million). The group also controls the famous luxury brand Baume & Mercier, plus a factory making gold watch cases, a factory making highly-specialised mechanical movements (Complications S.A.) and many other companies.”

But how Piaget got involved with Lemania is less interesting to me than why it did.

Lasalle’s legacy

The idea that Piaget would be interested in investing in a company that specialised in mechanical chronographs in the early 80s is hard to square.

Piaget didn’t seem to be operating as an entity that particularly cared about preserving the craft of mechanical watchmaking. Or being interested in making chronographs.

What Piaget does seem to have cared about throughout its modern history is thinness – and that’s perhaps why quartz was appealing to them.

Piaget was part of the Beta 21 project in the 60s. The movement that came out of it was ultimately too thick for Piaget’s tastes.

So in 1976 Piaget developed its own quartz movement, the 7P – the thinnest quartz movement available at the time at just 3.1mm.

The iconic Piaget Polo appeared in 1979. The vast majority of these watches at launch were quartz, powered by the 7P.

But quartz wasn’t the only thin watch game in town at the time. A vanishingly small number of Polo models in the original production run were powered by mechanical automatic movements. And it wasn’t Piaget calibers inside these models.

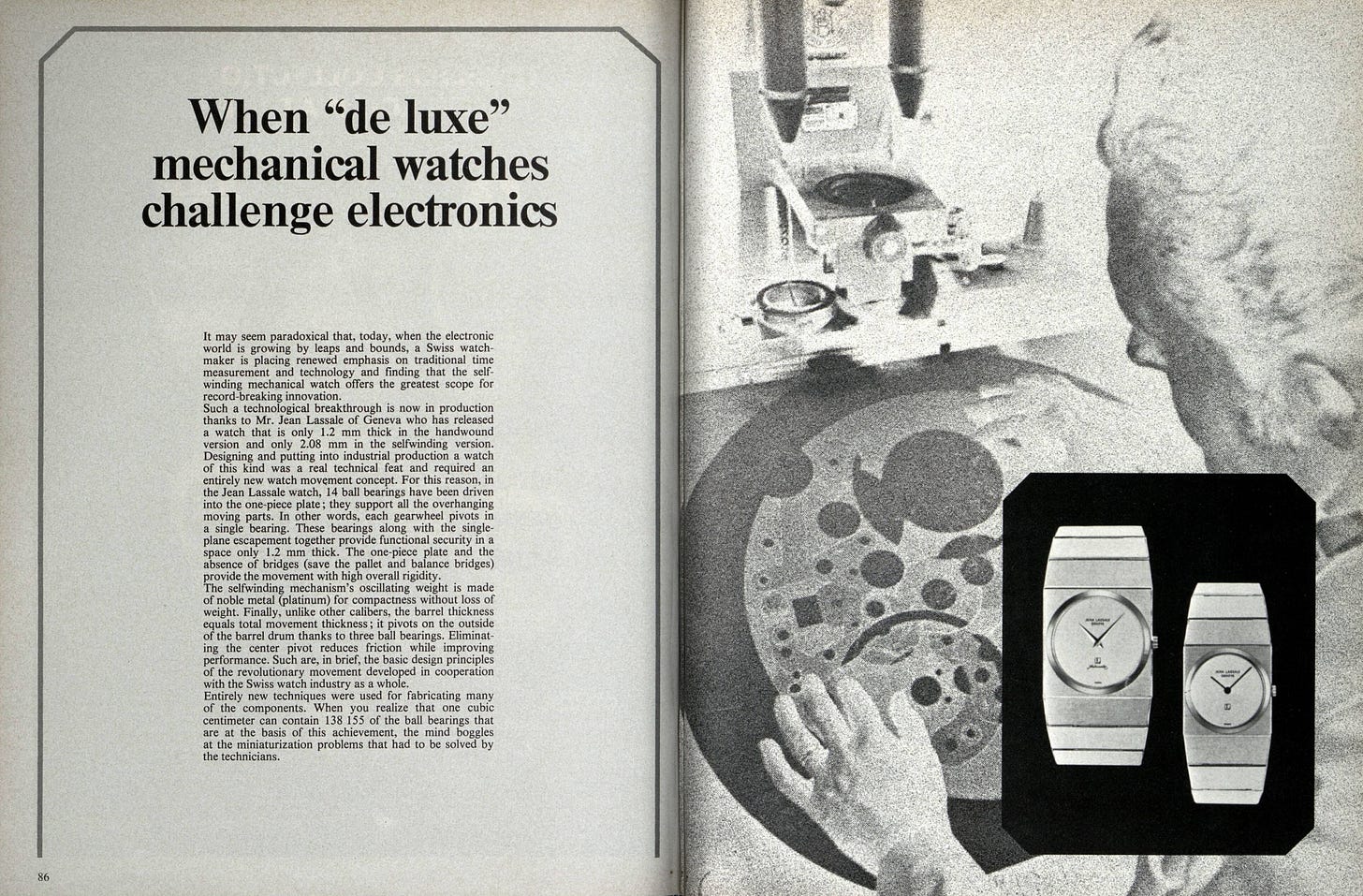

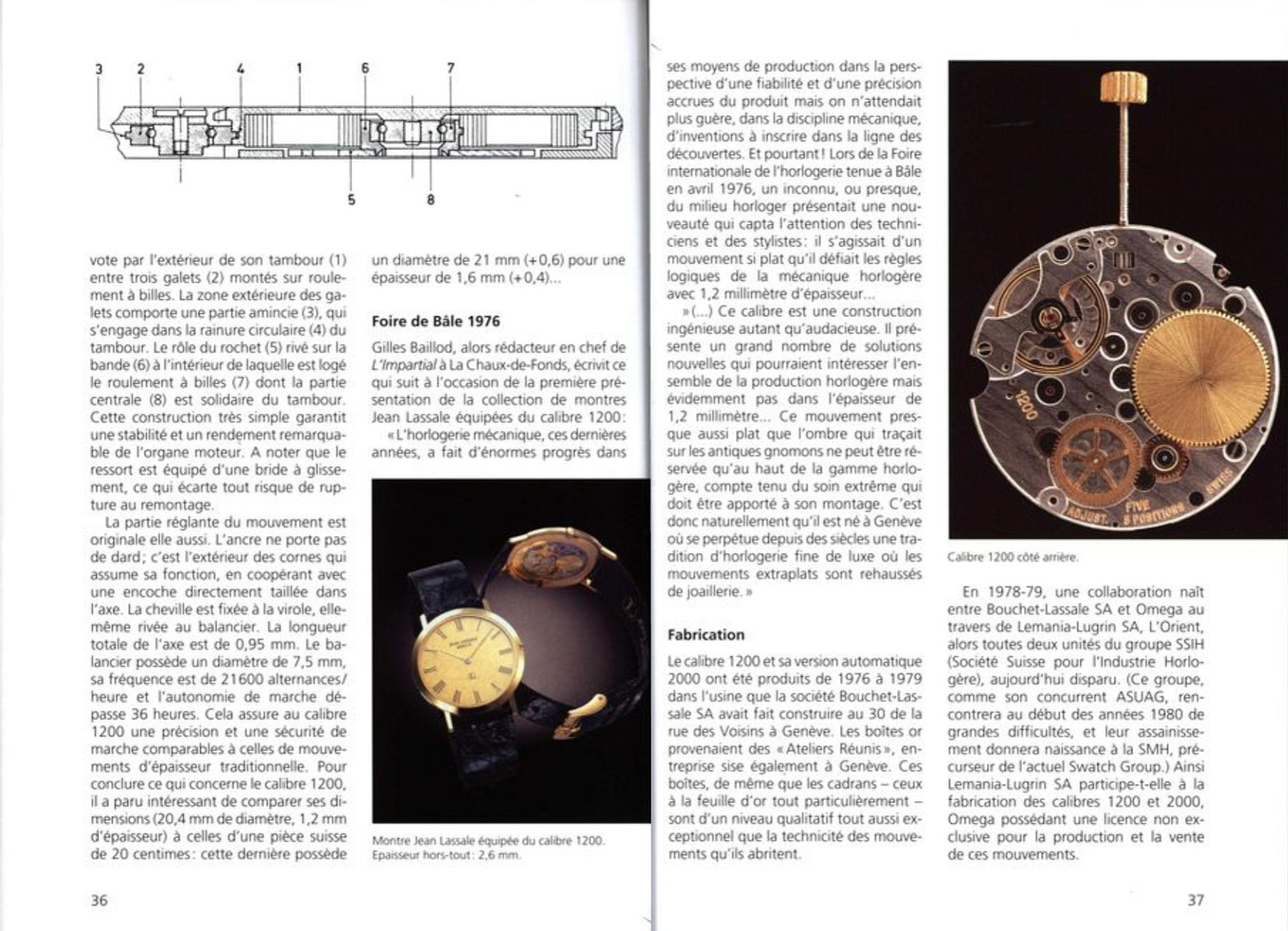

In the late 70s there was a watchmaker who was making a mechanical movement that was a mind-boggingly 1.2mm thin: Jean Lasalle’s 1200.

Piaget opted to use the automatic variant of the 1200 – the Jean Lasalle 2000 – in the automatic Polos, rather than one of their own. The 2000 was designated the “25P” in Piaget-speak. They also used the 1200 in other watches, labelled as the “20P”.

Piaget saw ultra thinness as an area of watchmaking they wanted to own. They had to have the thinnest watches available – it was a defensive moat in a troubled time for the industry.

And this leads us to the crucial reason I believe Piaget invested in Lemania: Lemania had recently acquired the exclusive rights to Lassale’s ultra-thin movement tech.

The acquisition of the patents is mentioned frequently in modern reporting and we have hard evidence that it happened, but it’s tricky to identify the exact timing of this particular IP transition.

There are some unverified quotes on the internet that suggest Lemania was already the manufacturer of Jean Lasalle’s Pierre Mathys-designed ultra thin movements before the patents were acquired. Some of the information on Jean Lassale’s citation-lacking Wikipedia entry is repeated in a 2003 article published by Swiss enthusiast association, Chronométrophilia.

“In September 1979, Bouchet-Lassale SA encountered financial difficulties such that its production was interrupted. In December of the same year, Claude Burkhalter, then director of Lemania-Lugrin SA, recalled during an internal meeting that “Omega has the possibility of acquiring the Jean Lassale brand.” This was indeed the period during which Omega was studying the opportunity to launch, under the name “Omega Louis Brandt,” a high-end collection, of which the two ultra-thin calibres could have been part.

Events then accelerated: the Jean Lassale brand was taken over by Seiko, while the technical files and patents associated with calibres 1200 and 2000 were purchased by Claude Burkhalter at the moment he created Nouvelle Lemania SA. Founded in 1981, this company took over the activities of Lemania-Lugrin SA and, from its very beginnings, produced the successors to the Jean Lassale 1200 and 2000: the Lemania calibres 1210 and 2010. These were mechanically and dimensionally identical in every respect, with the exception of the escapement wheel and the time-setting mechanism.

They were supplied exclusively to Piaget for as long as that company remained independent. Its subsequent move under Cartier’s control freed Nouvelle Lemania SA from this exclusivity, thereby allowing it to supply these calibres to Vacheron Constantin as well.”

While I’m perturbed by being unable to find verifiable cross-references for Lemania already working with Jean Lasalle, it does seem plausible.

Because here’s what we do know:

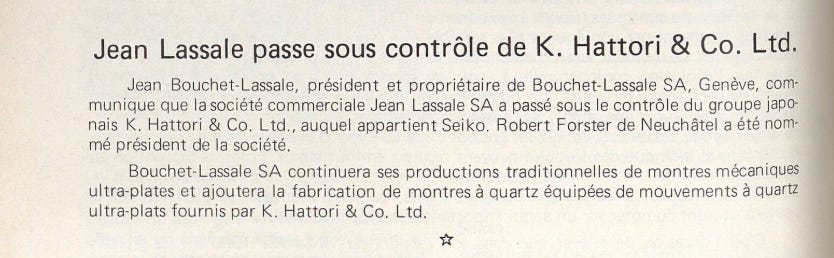

In 1980, the Jean Lasalle name was acquired by Seiko.

“Jean Lassale comes under the control of K. Hattori & Co. Ltd.

Jean Bouchet-Lassale, chairman and owner of Bouchet-Lassale SA, Geneva, announces that the commercial company Jean Lassale SA has come under the control of the Japanese group K. Hattori & Co. Ltd., to which Seiko belongs. Robert Forster of Neuchâtel has been appointed chairman of the company.

Bouchet-Lassale SA will continue its traditional production of ultra-thin mechanical watches and will add the manufacture of quartz watches equipped with ultra-thin quartz movements supplied by K. Hattori & Co. Ltd.”

On March 2, 1981 Lemania’s management buyout, which seems likely to have been backed by Piaget, was completed.

“A positive solution for Lémania

Lémania-Lugrin SA, a subsidiary of the SSIH group, has become independent. It has continued its industrial and commercial activities since March 2, 1981, under the corporate name “Nouvelle Lémania SA, Manufacture d’Horlogerie”, and employs around seventy people in L’Orient (Vallée de Joux).”

On July 16 1981, the US patent filed by Lasalle for its ultra-thin movement innovation was transferred to Lemania.

It seems extremely likely that the Piaget group helped save Lemania mainly to get access to the world’s thinnest mechanical movements of the time. I can’t think of any other compelling reason as to why Piaget would have bought a struggling chronograph maker – Lemania must have promised the deal included the Jean Lassale movement rights.

And it was that decision to invest in Lemania that meant the Piaget family were pulled into the deal to buy Heuer.

Enter EBEL

In late 1981, the Swiss Bank Corporation effectively closed Heuer’s accounts and set up a task force to restructure the company.

Lemania’s incentives are obvious: a newly independent chronograph manufacturer needs routes to market. Heuer has brand recognition and marketing muscle – and not many other options exist.

According to Jack Heuer, Lemania was primed to be part of an investment consortium he was putting together to take control of the company.

“I set out to find suitable investors and was quickly able to raise CHF 1.5 million in new capital. My in-laws agreed to support me with CHF 500,000. Claude Burkhalter, the CEO of Lemania, had immediately seen the manufacturing potential of the Calibre 410 in his newly-organised Lemania factory and agreed to participate to the tune of CHF 500,000. A third investor was Pierre-Alain Blum, the owner and CEO of EBEL in La Chaux-de-Fonds. At the 1982 Basel Watch Fair Pierre-Alain told me and my wife Leonarda, who was helping out with our Spanish- and Italian-speaking clients: “Jack, I know you need to refinance your company and I don’t want to see yet another family company go down the drain, especially such a famous and reputable brand like yours. I am ready to support you and will also chip in with CHF 500,000.“ In next to no time I had raised CHF 1.5 million with which to restart the company.”

And Jack goes on to say that it was EBEL’s involvement that led to Piaget getting more involved – and to him ultimately getting pushed out:

“I can only piece together what happened next from what I heard through the grapevine. When Mr. Valentin Piaget, the Piaget family member who oversaw their investment in Lemania, heard that Claude Burkhalter from Lemania, Pierre-Alain Blum from Ebel and I had verbally agreed to together invest CHF 1.5 million in the refinancing of Heuer-Leonidas, he must have immediately objected because Ebel was one of his main competitors.

On Friday, 4 June 1982, I had another one in a series of telephone conversations with Claude Burkhalter, the CEO of Lemania. He told me the entire refinancing would be taken over by Lemania, without help from EBEL and without any investment from my family. He added that Roventa-Henex was to convert its CHF 350,000 credit with Heuer-Leonidas into shares and went on to say that all this had been decided by Piaget, Lemania’s main shareholder.”

Now, this is all based on Jack Heuer’s account of events and there is some speculation involved, but if we assume in good faith that Pierre-Alain Blum did offer to invest, why would Valentin Piaget object?

EBEL is a name revered in some neovintage collector circles mainly because of the Sport Classic Chronograph, powered by Zenith El Primero-derived movements, that first appeared in 1977 on EBEL’s distinctive and innovative Wave bracelet.

Did Piaget see the EBEL Sport Collection as a competitor for its “sporty” Polo?

Perhaps, but it’s also worth noting that EBEL was deeply intertwined with another of Piaget’s direct competitors, Cartier, in the 70s – and was a leading manufacturer of Swiss Made quartz. In fact, it was EBEL who manufactured the (historically unlamented but successful at the time) Must de Cartier line. Logan Baker’s excellent EBEL piece for Phillips has more detail on this relationship.

It seems entirely plausible on this basis that Piaget didn’t want its Lemania subsidiary cosying up to EBEL and felt compelled to step in to help shape a different deal for Heuer.

Piaget-era Heuer

Piaget, having backed Lemania’s management buyout, wanted the chronograph maker to be successful and recognised Heuer could help make that happen.

But the evidence suggests the Piaget group did not particularly care about Heuer – the most compelling being that the company was sold to TAG in 1985, just three years after it was acquired.

Jack Heuer references a quote from former Piaget president Yves Piaget's autobiography released in 2010:

“One day Akram Ojjeh said to me, ‘Yves, I would like to get the initials TAG on a Swiss product.’ Akram Ojjeh was thinking of finding something in the Swiss watch industry and that is why he approached me. By chance, at that very moment the watchmaking company Heuer – famous in Switzerland since 1860 and one of the first to be official timer of the Olympic Games – found itself in a difficult situation. Heuer’s new owners were not particularly interested in remaining in the sports watch sector and there was a need to find some new financial owners. That’s how it came about that, together with Akram Ojjeh, I had the opportunity of creating the TAG Heuer brand, in other words joining the acronym ‘TAG’ with Heuer.”

Now, there’s some fairly interesting distancing happening here. Heuer’s “new owners” being, well, Piaget.

Funny how Yves just happened to be around to form TAG Heuer and serve on their board from 1985 to 1986 huh? Maybe there’s something lost in translation.

The other compelling piece of evidence for Piaget’s lack of interest in Heuer is the product development on their watch.

Storied collections withered away and Heuer was reoriented around watches that, although were selling well at the time, hastened the decline of Heuer’s brand reputation – something TAG Heuer is still contending with today.

Lemania got to install its 5100 movement in some Heuer cases (generally references that start “510”) but other than that Piaget-era Heuer watches are characterized by predominantly quartz lines developed by a company called Roventa-Henex.

Reclusive Roventa

Roventa-Henex (R-H) is a Swiss private label watch designer and manufacturer that makes watches for other companies – and crucially fulfills “Swiss Made” requirements.

R-H is intentionally discreet and keeps its clients confidential.

Everyone wants to imagine their Swiss Made watch is hand-crafted by farmers in the Vallée de Joux during harsh winters; R-H helps brands participate in that storytelling without having to, you know, actually manufacture watches themselves in Switzerland.

Jack Heuer’s autobiography is unusually open about how involved R-H was with Heuer. One particularly interesting revelation is that R-H was making all of Heuer’s diving watches in the late 70s, sales of which were “rocketing” by the early 80s – which meant Heuer owed R-H more than CHF 300,000 in unpaid invoices when the banks cut Jack off.

Norbert Schenkel, owner of R-H, was appointed by the Swiss Bank Corporation as a member of the task force that set out to restructure Heuer.

It seems R-H did quite well out of the restructure deal. It agreed to convert the money it was owed into shares on the basis that the restructured Heuer worked exclusively with them on anything that wasn’t a chronograph.

“What I do know from a letter from Roventa to the banking consortium is that Mr. Schenkel stipulated that, in return for his investment, Heuer-Leonidas had to purchase all its future supplies of diving and regular watches – i.e. with the exception of chronographs and stopwatches – from his own company, Roventa-Henex.

After Heuer-Leonidas was sold three years later to the TAG Group, the new management continued outsourcing production exclusively to Roventa-Henex. Thus Norbert Schenkel’s relatively-modest investment turned into a multi-million franc business for him and he later confessed to someone I know in Bienne that it was by far the best deal he had ever made in his life.”

Pulling the curtain further back on R-H’s relationship with Heuer is a more recent article: Jeff Stein’s excellent exchange with designer Eddy Burgener for Hodinkee in March 2025.

In the 1980s Burgener worked for R-H designing watches for Heuer (and then TAG Heuer). He designed the Heuer 2000 and 3000 series, an evolution of Heuer’s dive watch line.

He also designed the Executive, an attempt to make a “flatter” dive watch with a more elegant look. The Executive line features a rotating, partially-lumed bezel that fits around the case rather than on the front of it. The quartz Executive was 2x the price of Heuer’s Lemania-powered chronographs at launch.

As with the aforementioned Airline 24 H GMT, the Executive has a very distinctive look. And not one that everyone loves.

At this point I should probably confess that I am a fan – and own examples of – the Airline and the Executive. The oddball designs and stories they tell around this transitional period for Heuer are entirely my jam.

And they are perhaps the two watch lines that are most representative of Piaget-era Heuer. They appeared and then disappeared from the company’s catalogues as quickly as Piaget bought and then sold Heuer to TAG.

The Airline and Executive collections both first appear in Heuer catalogues in 1985. Meaning they were most certainly designed and developed when the company was owned by Piaget.

They make their final appearance, now branded with the TAG Heuer logo, in the 1988 catalogue. Unloved and quickly forgotten.

Was Piaget behind the Formula 1?

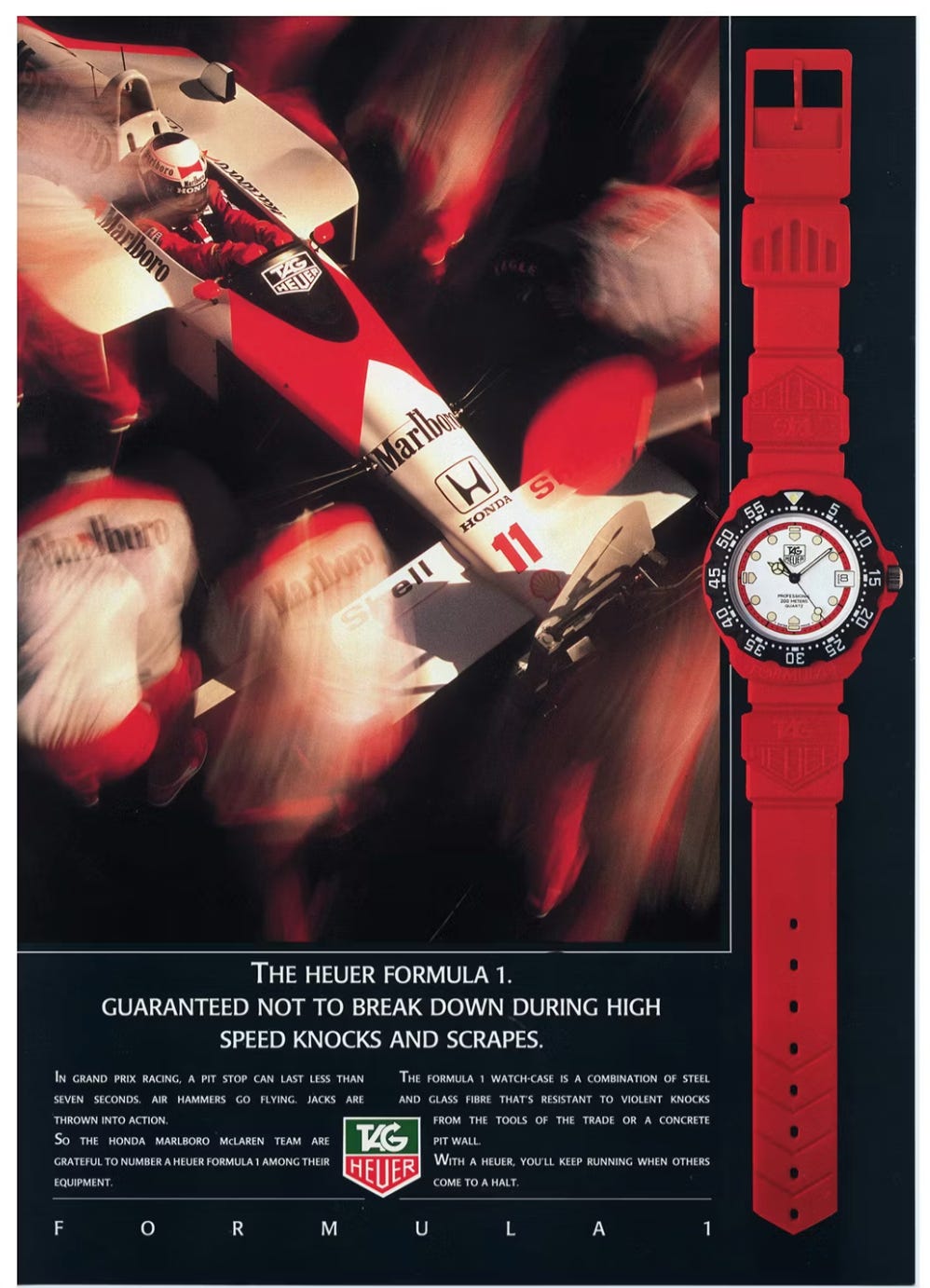

There is of course one TAG Heuer watch from the mid 80s that is fondly remembered by many people: the Formula 1.

Conventional wisdom says that TAG came in and commissioned the Formula 1 because of its connection to the sport, but was it actually Piaget that kicked off work on this incredibly popular icon of a watch?

In Burgener’s Hodinkee interview he says

“the brief from Heuer, in Spring 1985, was to create a new watch that was fun, colorful, and young.”

He also shares a sketch of the Formula 1, branded TAG Heuer, helpfully dated August 5, 1985.

Later in the interview he goes on to say:

“We began working on the new watch in Spring 1985, and if my memory is correct, we called this project the “diving watch for young people.” The design brief did not mention racing or Formula 1, but the name was added to the watch during the design and development process. In my sketches from 1985, you can see that the bottom of the case is marked “location for brand name.”

Jack Heuer recalls reading about the sale to TAG on June 29, 1985. Europa Star archives give even cleaner dates.

In its July-August 1985 Trade Bulletin (Issue #991) there’s what seems like a fairly benign update:

“Heuer–TAG partnership

After a period of major difficulties, the Heuer manufacture is moving forward again.

Firmly taken in hand by the management of Nouvelle Lemania S.A. in L’Orient, the Biel/Bienne-based company succeeded in doubling its turnover in 1984 and is announcing even more positive results for the current year.

From then on, its association with the powerful TAG group (Techniques d’Avant-Garde), based in Luxembourg and specializing in maritime and aeronautical navigation as well as automobile racing, opens up highly promising prospects.”

What’s really interesting, however, is the publication of a clarification in Trade Bulletin Issue #992 from September 1985:

“About HEUER…

Clarification

In our Bulletin No. 991, we published an article devoted to the Heuer–TAG partnership.

In this connection, the HEUER company has asked us to publish the following clarification:

On July 1, 1982, the HEUER company was taken over by the PIAGET company and from that date formed part of that group.

The LEMANIA company was a shareholder of the company.

On June 1, 1985, the TAG group acquired the majority of the company’s shares; its management is currently ensured by Messrs. Willy Monnier, Managing Director, and H. Arni, Sales Director.

We ask our readers to take due note of these clarifications.”

This clarification is particularly notable as it:

Gives us a definitive, precise date for when TAG acquired Heuer – I haven’t seen this widely reported elsewhere

Reveals without question that Piaget owned Heuer entirely – Lemania was a shareholder

So what does that mean for the Formula 1?

The evidence suggests it was Piaget-era Heuer that briefed R-H to create it, then TAG Heuer came in and named it, created a motorsport narrative around and brought it to market under those auspices.

Piaget at the point of inception, TAG at distribution.

The Formula 1 – a dive watch with a motorsport name – instantly makes more sense when you look at it through this lens.

What it all means

Knowing that Piaget briefly owned Heuer is a great piece of trivia. But delving into the broader story offers so much more.

Realising that Piaget didn’t really want to own Heuer and that they got pulled into that ownership because of ultra-thin watchmaking adds depth.

Then there are the pop culture overlays. The only Heuer watches ever to feature in a Bond movie are from the Piaget-era. The Formula 1 – the most popular icon of 80s/90s TAG Heuer – likely begins as a Piaget-era brief.

Zoom out and the whole thing becomes a case study for understanding what was happening in the watch industry at the time – and how it informs our understanding of watches today.

Some companies were radically restructuring in an attempt to survive the quartz crisis.

Some were leaning heavily into quartz; some were hedging their bets and some saw positioning mechanical watches as hand-crafted luxury items as the way forward (Biver’s Blancpain, for example).

Quartz lit the fuse on the ultra-thin wars, leading to Piaget’s acquisition of Heuer and igniting an arms race that still runs today.

The cast of characters embroiled in this tale – and how they have evolved – is absurdly dense.

Modern TAG Heuer shows little love for the Piaget-era, choosing to focus on reviving older heritage collections such as the Carrera and leaning back into its F1 connection that came after Piaget’s ownership.

Piaget and Cartier, once rivals, are now part of the same group, having been acquired by Richemont. Piaget continues to pursue ultra-thinness as an ideal.

EBEL is not what it was, but its commitment to reviving the mechanical chronograph in the 80s was critically important for the watch landscape today.

Lemania eventually returned “home” to the Swatch Group – and is now operating as Manufacture Breguet.

And one name that I haven’t mentioned yet as part of this story – but is intrinsically intertwined – is Chronoswiss.

Gerd-Rüdiger Lang is sometimes mentioned in the same breath as Günter Blümlein (IWC, Jaeger-LeCoultre), Jean-Claude Biver (Blancpain) and Pierre-Alain Blum (EBEL) as one of the visionaries who believed the path out of the quartz crisis for the Swiss watch industry was to lean harder into mechanical watchmaking rather than jumping on the quartz bandwagon.

According to Jack Heuer’s autobiography, in the course of negotiations to reduce his company’s overheads, Lang convinced Heuer to fire him from their after-sales service department so he could take unemployment payments and train as a master watchmaker (while continuing to do some servicing for Heuer on the side).

Lang founded Chronoswiss some years later. In 1987, Chronoswiss released the first serially-produced regulator wristwatch. In 1995, the first serially-produced skeletonized automatic chronograph. Mechanical firsts that can be traced back to this same corporate restructure.

The emergence of Chronoswiss reinforces my central point: Piaget’s unlikely acquisition of Heuer explains a truly transitional moment for the watch industry – and its impact is still clearly visible more than 40 years on.

With thanks and gratitude to:

The Surprising Origins Of TAG Heuer’s Formula 1 Watches by Jeff Stein. [2025]

The Fine Print: Ebel Is Back! A Complete Collectors’ Guide To Complicated Ebel Wristwatches Of The Late 20th Century by Logan Baker. [2024]

Ultra Thin: What It Is, Why It Matters, And Who Does It Best (Part 2) by Jack Forster. [2016]

OnTheDash (Jeff Stein again) for hosting The Times of My Life — Jack Heuer’s Autobiography.

A Collector’s Guide To The Original Piaget Polo by Tony Traina. [2024]

The Europa Star archives.

This is a fantastic article Chris. I had no idea of the Piaget connection with Heuer!